Design choices for Vision-Language Models in 2024

Written on April 16th, 2024 by Théo Gigant

Illustration: Truisms (Jenny Holzer, 1977–79)

Vision and language models are the new shiny thing in the AI space, delivering mind-blowing results at a very fast pace.

Some are big, some are small, some are very complex machinery, some are as simple as it gets, some can only process one image, some whole hour-long videos, others can also generate images.

One thing we can learn from all these different models is the choices that were made and the results they yield. Especially, in this blog post we will focus on the automatic understanding of vision and language by describing some of the popular designs that were studied in the recent developments of Vision-Language Models. For a more hands-on blog post on vision-language models, please check Merve Noyan and Edward Beeching’s blog post on HuggingFace.

Vision and language in a shared latent space

CLIP is a simple but effective framework that jointly learns a vision and a text encoder, trained to project images and captions in a shared latent space in which an image is close to its caption.

Illustration: CLIP contrastive pre-training (OpenAI Blog)

It is a building block of most recent multimodal vision-language models, eg the text encoder in text-conditioned image generation such as all the Stable Diffusion models, or the image encoder in language and vision chatbots such as LLaVA.

In the frameworks that aim at understanding language and vision, the ViT image encoder from CLIP (or newer CLIP-inspired techniques such as SigLIP) is often used as the vision backbone.

A key advantage is that the latent tokens representations in CLIP’s ViT might have some sort of a cross-modal / synaesthetic ability, by already being mostly aligned with their captions.

“Mostly”, because the latent representation of the image is aligned to the latent representation of the text, that went through the tokenizer and the transformer-encoder, while in most scenarios the encoded image is fed to a language model among freshly-embedded text tokens.

In order to re-align visual tokens with the text tokens, and, optionally, compress, focus or select the visual information that will be forwarded to the language model, the encoded image tokens are processed by a “Visual Abstractor” model.

Leveraging and aligning pretrained models with a “Visual Abstractor”

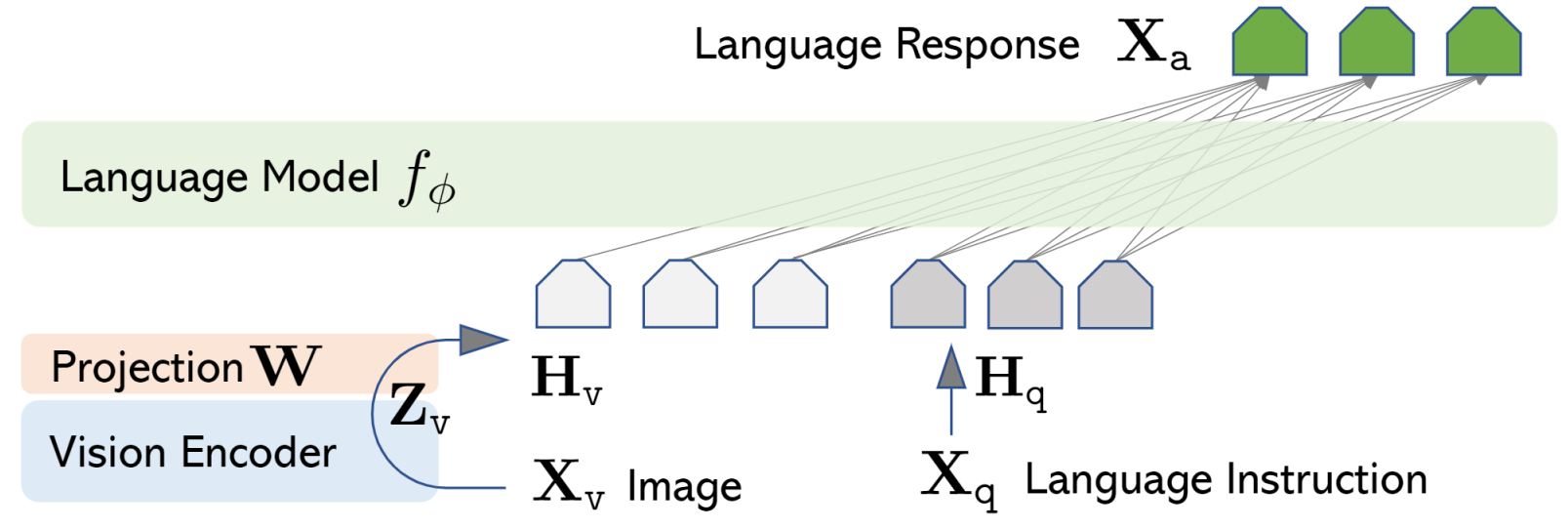

When using the image encoder from CLIP, the images are mostly pre-aligned with text and we could just map the CLIP latents to the text token embeddings, with a minimalistic projection layer that will be trained on image/caption pairs. This is the idea behind the LLaVA framework.

Illustration: LLaVA architecture (LLaVA Blog)

Illustration: LLaVA architecture (LLaVA Blog)

The authors call this mapping the “projection”, and it is trained on image/caption pairs while keeping the vision and language models frozen. This projection and the language model are tuned during “visual instruction tuning”, a second, more expensive, training stage aimed at teaching the model to follow instructions on visual tasks.

In the first LLaVA, this abstractor was a simple linear projection. In subsequent versions (LLaVA 1.5 and 1.6/NeXT), it was swapped for a more expressive Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP).

While minimalistic and effective, this “projection” strategy has the disadvantage of keeping the number of tokens from the encoded image, ie $16*16=256$ tokens with ViT. For some applications –say video understanding– the total number of tokens might blow up, and be very redundant too. In such situations, a “Visual Abstractor” can select the information from a varying number of images with a fixed tokens budget, with popular choices being the Q-Former (BLIP-2) or the Perceiver Resampler (Flamingo) abstractors. Both are using learnt queries and attention to select the salient visual information for a given token budget, but Q-Former is also conditioned on input text.

Cha et al studied other visual abstractor strategies more in-depth, based on convolutional neural networks (C-Abstractor), or deformable attentions (D-Abstractor), in addition to adaptive average pooling which allows to select the number of output tokens.

Li et al proposed to only keep two tokens for each frame for video understanding: one that only encode the frame information (dubbed “content” token), and another one, conditioned on input text, aiming to encode the contextualized information (dubbed “context” token).

All these ideas rely on aligning and filtering multiple pretrained models to leverage their multimodal capabilities.

There are multiple ways to merge the modalities: Alayrac et al opted for gated cross-attention in-between Transformer blocks for Flamingo, while for LLaVA, Liu et al prefered to add the vision embeddings as new tokens to the language model, which architecture was kept as is.

Depending on the choice, images can be seen as an additional information which can be referred to by text tokens, or as a bunch of tokens that can be concatenated with, and processed similarly to, text tokens. When taken to the extreme, the latter is similar to modeling images as a foreign language.

Are images a foreign language?

As shown empirically by Dosovitskiy et al with their ViT model, images can be processed with the same architecture as text, with state-of-the-art performance. The image is split into patches, that are embedded and processed by a language model as if they were text tokens. Effectively, an image becomes a foreign language, and Wang et al tested it quite litteraly. Their BeiT 3 model follows the ViT architecture with a multimodal twist, as the model is trained from scratch with image and text tokens processed in the same model but with different experts.

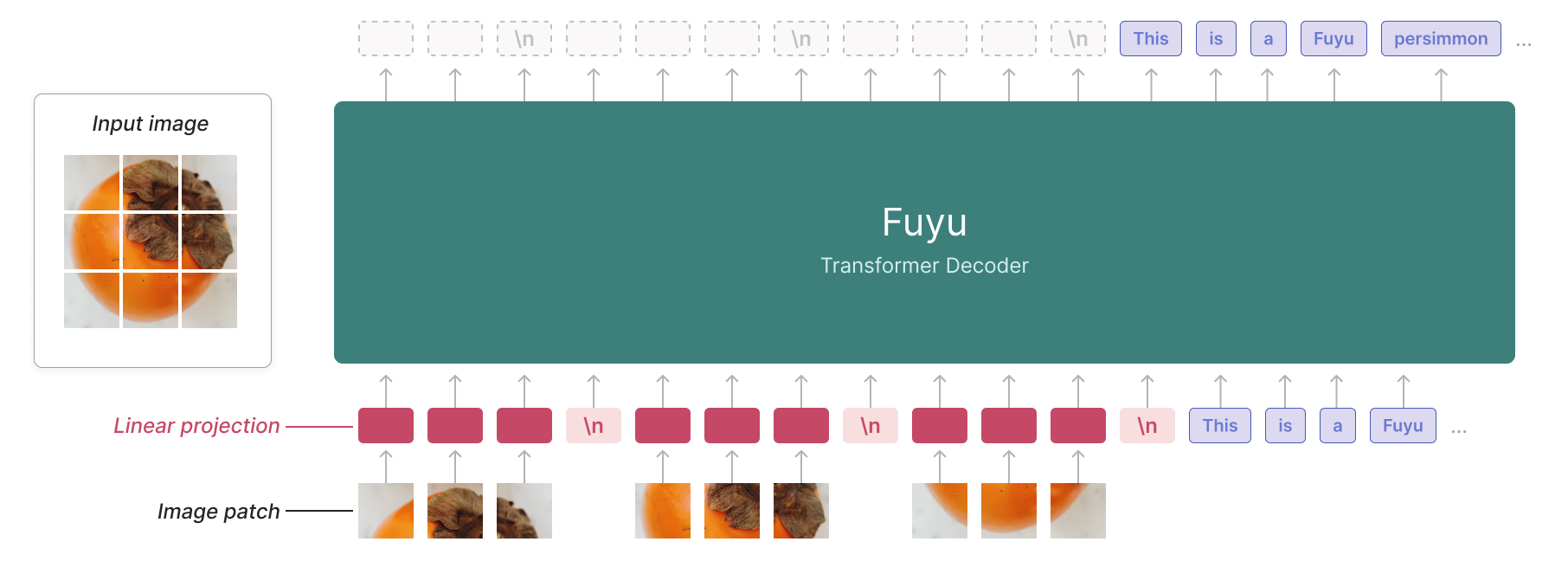

Halfway between aligning pretrained models and training a model with all modalities, falls Adept’s Fuyu framework. They simplified both the architecture and training procedure by feeding the image patch embeddings as is to a language model. With that framework, there is no need to think about how to scale the vision encoder vs the language model, or what training stages to do and in what order, and the model is able to work with images of varying resolutions. This last particularity was then improved upon by Li et al in their OtterHD model.

Illustration: Fuyu architecture (Adept Blog)

Illustration: Fuyu architecture (Adept Blog)

The authors claim that the Fuyu framework is “easier to understand, scale, and deploy”, but give no information about the amount of data used or the cost for training such model. It would be no surprise if it is orders of magnitude more than with the LLaVA framework, for comparable results.

ARE images a foreign language? The argument of granularity

An aspect we might reflect on is the granularity of modalities.

An earlier work on multimodal models by Alayrac et al proposed to merge the modalities at different points depending on their granularity. Audio and vision are treated as fine-grained, while text is more coarse-grained.

The paper reads:

This strategy is based on the observation that the visual and audio spaces are fine-grained (there are many visual or sounds of guitars that might be really different to each other) while the textual domain is more coarse as its goal is to abstract away details (e.g. a single “guitar” word).

This idea weighs in favor of pre-processing the images first, eg by using an image encoder before feeding the resulting embeddings to the language model.

However, are we sure to know how finer-grained vision is, compared to text? And do all text tokens have the same granularity?

One might argue that some words with lots of different meanings depending on the context have a different granularity compared to stop-words for instance. An example that one might interpret in this direction is the recent Mixture-of-Depths work by Raposo et al showing that all tokens don’t need the same model depth.

All visual tokens are not as fine-grained as well, with the example of documents vs real-world pictures.

Maybe in this situation, a better solution will be to just throw everything at once in the model, and let it figure out how much processing each token needs.

Putting everything together

To summarize the vision-language model designs we discussed so far:

Vision encoding strategies:

- Pretrained vision encoder: leverage a pretrained –and pre-aligned– model (eg LLaVA)

- Raw image patches: no loss of information, end-to-end training (eg Fuyu)

Vision-language alignment strategies:

- Projection: map the visual embeddings to align with the language model (eg LLaVA)

- Resampling: resample all the visual information in a fixed number of tokens (eg Flamingo)

- Text-conditioned resampling: resample all the visual information in a fixed number of tokens, given a text query (eg BLIP-2)

Multimodal fusion strategies:

- Interleaved vision and language tokens: process the vision embeddings as if they were text embeddings (eg LLaVA)

- Modality experts: language and vision embeddings are processed by different experts in the language model (eg BeiT 3)

- Cross attention: language tokens can attend to image embeddings using cross-attention in-between transformer blocks, introduce lots of new parameters (eg Flamingo). This strategy was mostly dismissed in recent vision-language models developments, likely because it introduces a lot of new parameters.

And some examples of Open Source Vision-Language Models (as found in this blog post) and the choices they made:

| Model name | Vision encoding strategy | Vision-language alignment strategy | Multimodal fusion strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

LLaVA-NeXT (llava-v1.6-vicuna-7b) |

Pretrained vision encoder (clip-vit-large-patch14-336) |

Projection (MLP) | Interleaved vision and language tokens |

DeepSeek-VL (deepseek-vl-7b-base) |

Two pretrained vision encoders (ViT-SO400M-14-SigLIP-384 and sam-vit-base) |

Projection (MLP) | Interleaved vision and language tokens |

moondream2 (moondream2) |

Pretrained vision encoder (ViT-SO400M-14-SigLIP-384) |

Projection (MLP) | Interleaved vision and language tokens |

CogVLM (cogvlm-base-490-hf) |

Pretrained vision encoder (EVA02_CLIP_E) |

Projection (MLP) | Modality experts |

Fuyu-8B (fuyu-8b) |

Raw image patches | Projection (Linear) | Interleaved vision and language tokens |

Kosmos-2 (kosmos-2-patch14-224) |

Pretrained vision encoder (clip-vit-large-patch14-336) |

Resampling | Interleaved vision and language tokens |

Qwen-VL (Qwen-VL) |

Pretrained vision encoder (CLIP-ViT-g-14-laion2B-s12B-b42K) |

Resampling | Interleaved vision and language tokens |

Yi-VL (Yi-VL-34B) |

Pretrained vision encoder (CLIP-ViT-H-14-laion2B-s32B-b79K) |

Projection (MLP) | Interleaved vision and language tokens |

Idefics (idefics-80b) |

Pretrained vision encoder (CLIP-ViT-H-14-laion2B-s32B-b79K) |

Resampling | Cross attention |

Idefics 2 (idefics2-8b) |

Pretrained vision encoder (siglip-so400m-patch14-384) |

Resampling | Interleaved vision and language tokens |

What decision works best for different use cases?

An important decision is the pretrained models we are basing our vision-language model on. We didn’t really talk about the base language model, but their context-size, and linguistic capabilities (what languages can it process? is it able to read and write code?) are essential in the downstream performances. Similarly, if there is a pretrained vision encoder, its image resolutions compatibilies can be a problem in some tasks, and the domain it was trained on (photographs, documents?), are key attributes to take into account.

The design choices of the whole vision-language model architecture also need to be done bearing in mind the downstream use case.

In video understanding tasks, using a projection alignment strategy can lead to a huge number of input tokens with a lot of redundancy. On a limited context length budget, resampling (text-conditioned or not) might be a cost-effective way to focus on the more salient information in the visual inputs.

For tasks that require to focus on fine details in the input images, it could be a good idea to crop parts of the input, input multiple resolutions at once, or to dump the whole pretrained image encoder to more easily account for varying resolutions.

When it comes to training the resulting model, the choice of the datasets used is also a huge deal, it will shape the performance on some tasks such as OCR-free document understanding or understanding of visual prompts.

What about benchmarks?

Benchmarks might be useful for making your choices, but at the moment extensive experiments on vision-language models design choices are rare and biased towards image captioning tasks.

due to the nature of common evaluation being heavily tailored to captioning problems (3 out of the 8 benchmarks are captioning), captioning data notably lifts zero-shot performance

(Extract from MM1: Methods, Analysis & Insights from Multimodal LLM Pre-training)

Models benchmark results are also not very insightful to compare vision-language model designs because they are based on different language models and vision encoders with varying performances, and trained with very different amount of compute and data.

This being said, here are some ways to compare available vision-language models on some benchmarks:

- The OpenVLM Leaderboard shows the scores of various models on different vision-language benchmarks.

- The Vision Arena gives Elo ratings of vision-language models based on blind voting from users.

Where are Vision-Language Models headed?

Obviously, no one can know for sure. But there is something that we can take from the bitter lesson: all these tricks to cleverly leverage and align pretrained models of different modalities, and to filter and focus the visual content for a given token budget, are temporary solutions. At some point, we might have models trained end-to-end to figure everything by themselves based on statistics of more-and-more massive datasets. eg Fuyu-MoD-style with infinite-context.

For the time being, we better be thoughtful and deliberate in our choices, in order to design useful vision-language models for different tasks with limited training budgets and computations.