Language Models' Language: Prompts & Latent Spaces

Written on June 14th, 2022 by Théo Gigant

Illustration: The Tower of Babel (Bruegel, 1563)

Language models are everywhere and nowhere near slightly conscious. They are modeling the statistics of language and outputs what they learnt to be the most probable.

As such, they reproduce, and even exacerbate, biases in data they were trained on.

On the model card for his controversial GPT-4chan, Yannic Kilcher wrote:

This is a statistical model. As such, it continues text as is likely under the distribution the model has learned from the training data. Outputs should not be interpreted as “correct”, “truthful”, or otherwise as anything more than a statistical function of the input.

Language Models speak a Language of their own which was engineered to be as human-like as possible, yet some flaws remain.

Those reasons are why everyone who wants to use these models might benefit from acquiring some knowledge about machine learning.

The importance of phrasing

If you follow the news about language models, you may have encountered this table:

It’s an extract from the paper Large Language Models are Zero-Shot Reasoners, and it shows that large language models’ performances are very much dependent of the prompt chosen.

The idea of knowingly chosing a prompt to get better results is called “prompt engineering”. To some people this name can be misleading since it’s arguably not really comparable to engineering, and is more related to phrasing.

In The Problem with Prompt Engineering , Bakz T. Future writes:

Prompt engineering itself may be a temporary band-aid solution and term we are just throwing out there until the language models get better and entirely human-like.

You can find a few models that do text-conditionned image generation. This means that using a text description as a prompt, the model will generate a brand new, never seen before, image.

Wikiart Diffusion Mini is one of those models, and it was trained on the WikiArt dataset comprised of tens of thousands of paintings. You can try out a demo yourself on Hugging Face’s Spaces.

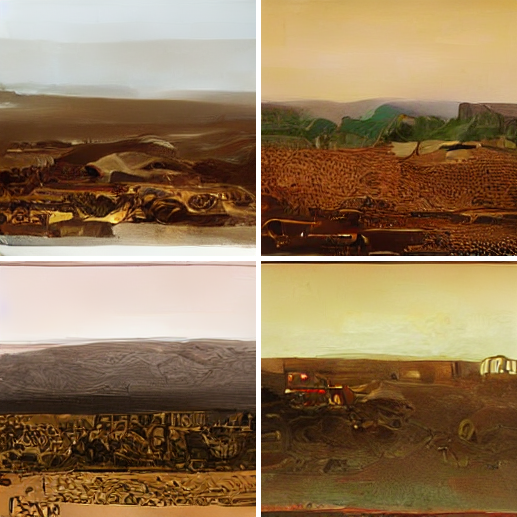

We will give texts as prompts to the model and show 4 images that were generated with each description:

- Prompt 1 =

"A martian landscape"

Well, those are not really good looking…

Maybe with a better description, the results can be a little bit more convincing!

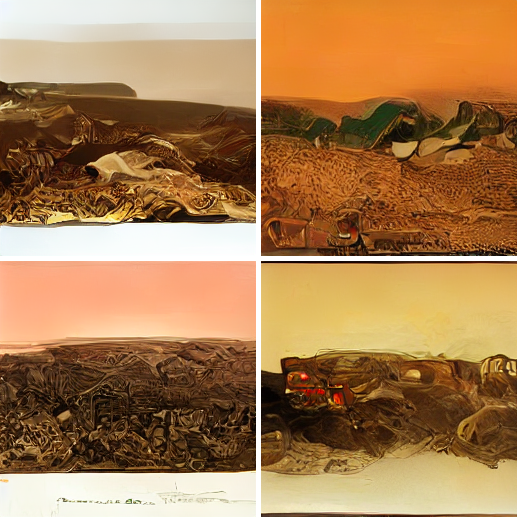

Since this model was trained exclusively on paintings, we may have better results going with a prompt that explicitely describes a painting.

- Prompt 2 =

"A martian landscape painting, oil on canvas"

This one is noticeably better.

We may go for a specific style and still get satisfactory results with a relevant prompt.

For example if we want the painting to be painted in the style of Vincent Van Gogh we can specify it:

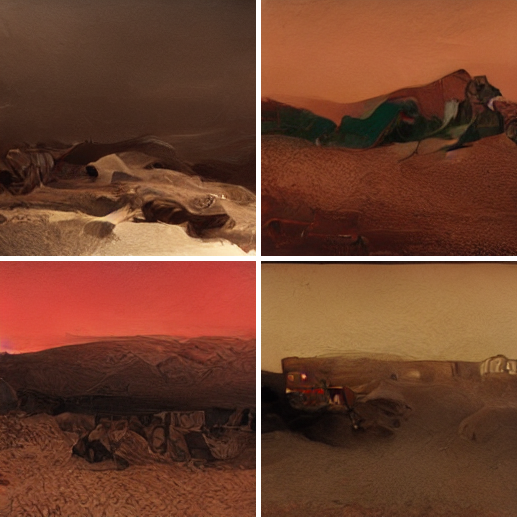

- Prompt 3 =

"A martian landscape painting, in the style of Van Gogh"

If you have read a little bit about prompt engineering for text to image models, you may want to go for a prompt with keywords such as Photorealistic, Unreal Engine, trending on ArtStation, … But let’s see if it works in this case.

- Prompt 4 =

"A photorealistic martian landscape

- Prompt 5 =

"A realistic photograph of a martian landscape, Unreal Engine, trending on artstation"

Arguably, the two latter prompts (4 & 5) don’t give results as good nor as close to the prompts as the two that came before (2 & 3).

This may be because these descriptions do not match the images that this model was trained to generate.

This is what is called distribution shift (or domain shift) between training and inference.

Example: Here is an example of a domain shift in Computer Vision, the images from domain 1 are studio photographs taken on a white background, where the images from domain 2 are photographs with ground and wall as a background.

The model was trained on specific data, and if the data seen during inference is from a different domain, it might not generalize well.

If your model has only seen English words during training, it will not magically become fluent in French during inference.

Now that we have seen this, we have the intuition of what the choice of prompt really is: a way to guide the model to do what we want by talking to it in a language it understands.

But to do this, we need to understand what the model’s language is. Better still, what the dataset domain looks like.

Prompting

Illustration: Diagram of T5’s text-to-text framework. Every task considered uses text as input to the model, which is trained to generate some target text. This allows to use the same model, loss function, and hyperparameters across a diverse set of tasks including translation (green), linguistic acceptability (red), sentence similarity (yellow), and document summarization (blue).

The idea behind finding a good prompt is to find templates that are specific and trigger the outputs we want for a model. For instance for T5, the template "translate English to German: {text}" lets the model know that we want it to translate the following text to German. In the case of T5 it was engineered this way in the training dataset. But in most case, it might just come from specific phrasing that were not intentionnaly put in the dataset.

For example you can trigger a model trained on reddit (such as GPT-2) to do summarization by prompting "{text} TL;DR". This time, this specific phrasing was just found to appear a lot in the training data. In Reddit posts, the keyword “TL;DR” (Too Long; Didn’t Read) is usually followed with a short bullet points summary of the text before. After training on this data, a language model reproduces this behaviour.

Examples with GPT-3

Glossary from Prompt Engineering Tips and Tricks with GPT-3 :

- Model: The LLM being used, GPT-3 in this case.

- Prompt: The text given to the language model to be completed.

- Zero-shot: A prompt with no examples, e.g.

The name of a character from Lord of the Rings is:or[English: "Hello!", French: "- Few-shot: A prompt with one (1-shot) or more (n-shot, few-shot) examples.

And an example of a 4-shot prompting for GPT-3, from the same article:

This is a list of startup ideas:

1. [Tag: Internet] A website that lets you post articles you've written, and other people can help you edit them.

2. [Tag: Home] A website that lets you share a photo of something broken in your house, and then local people can offer to fix it for you.

3. [Tag: Children] An online service that teaches children how to code.

4. [Tag: Financial] An online service that allows people to rent out their unused durable goods to people who need them.

5. [Tag: Machine Learning]

GPT-3’s output for this prompt is:

An online service that lets people upload a bunch of data, and then automatically builds a machine learning model based on that data.

I don’t think there is any go-to method to find the best prompts for a specific model. But people are exchanging about this:

- for GPT-3

- for Boris Dayma’s DALLE-mini

Because of the internet hype around it at the moment, not every discussion for the latter are relevant for prompt engineering, most of them are about memes or people being mad at each other, but some people are still sharing some interesting prompt experiments.

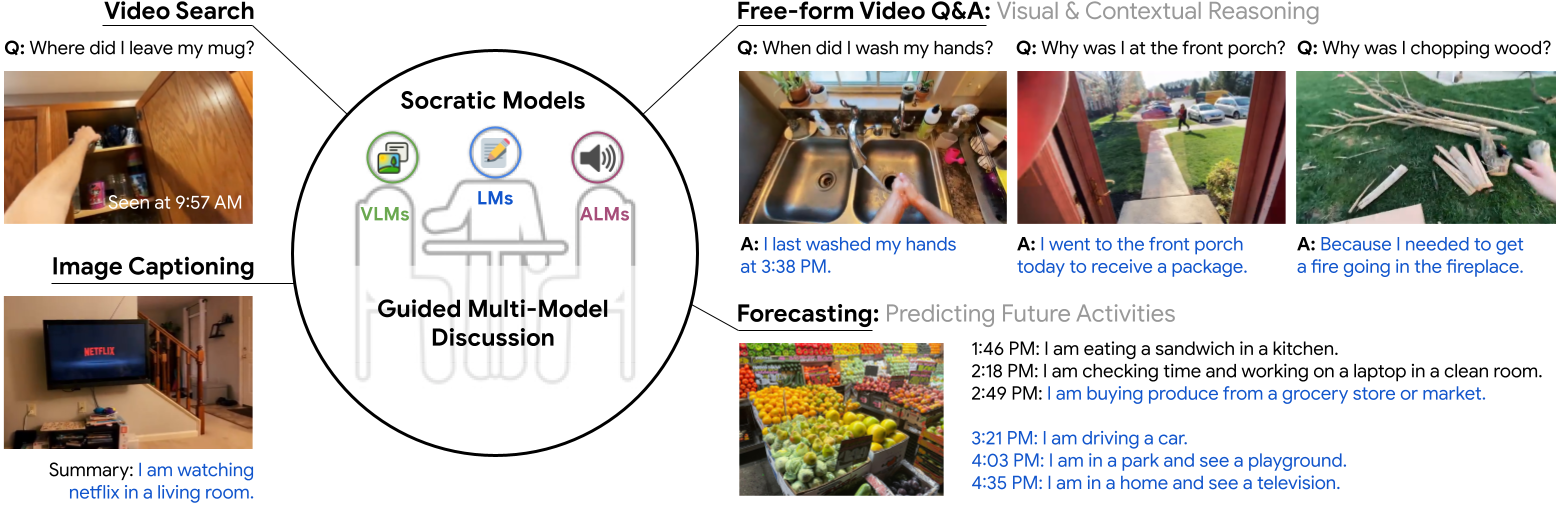

Socratic Models

This idea that the way you phrase your query will have a great influence on the results is found to be true for lots of models. And models trained on different domains and/or modalities have very different capabilities. For instance visual language models (eg CLIP) are trained on image/captions pairs and thus are good at highlighting the similarities between images and texts, but are not trained on as much text as a pure Large Language Model (eg GPT-3).

Socratic Models suggests a framework to compose models trained on different domains (eg: modalities) in a zero-shot fashion to capture new multimodal capabilities.

In other words, it is a way to connect models together via well-chosen prompts allowing to create a super-model which can excel at various multimodal tasks without the need for fine-tuning.

The Model’s Language

Hidden vocabulary

Sometimes, some weird prompts might offer very good results. It might be hexadecimal colors that allows to have more control over the results, some magical pieces of texts like trending on artstation, unreal engine that drastically improve the quality of the images. Or even some weirder words, that don’t appear to align with any known human language.

The text-to-image synthesis model DALLE-2 was found to have developped such a hidden vocabulary.

As shown in their article Discovering the Hidden Vocabulary of DALLE-2 , Daras et al discovered that DALLE-2 can create images of objects consistently with an absurd prompt.

The paper reads:

A known limitation of DALLE-2 is that it struggles with text. For example, text prompts such as:

An image of the word airplaneoften lead to generated images that depict gibberish text. We discover that this produced text is not random, but rather reveals a hidden vocabulary that the model seems to have developed internally. For example, when fed with this gibberish text, the model frequently produces airplanes

DALLE-2 seems to have a hidden vocabulary that can be used to generate images with absurd prompts. For example, it seems that

Apoploe vesrreaitaismeans birds andContarra ccetnxniams luryca tanniounons(sometimes) means bugs or pests. We find that these prompts are often consistent in isolation but also sometimes in combinations.

Sometimes, those weird prompts come from biases in the dataset. That is the case of the trending on artstation, unreal engine keywords, that are consequences of the image/text pairs datasets that were often automatically annotated. In these datasets, captions containing those keywords are often paired with higher quality images.

In the case of the hidden vocabulary of DALLE-2, unknown words consistently refers to some specific objects. The cause is thought to be random bias in CLIP that encodes these words in a similar way as the object it refers to (The CLIP encoding for Apoploe vesrreaitais is close to the one for birds).

There also are some discussions about interesting experiments of the same type for Boris Dayma’s DALL-E mini.

For a more comprehensive study on prompt engineering for text-to-image synthesis, make sure to take a look at A Traveler’s Guide to the Latent Space. In this article, Ethan Smith describes lots of techniques to take the most out of Disco Diffusion, a popular set of tools to create art using AI. Another in-depth guide to prompt engineering for DALLE-2 is dall-ery gall-ery’s DALL·E 2 Prompt Book

Latent Space

The output of CLIP encoders is a latent vector, ie a vector from a latent space. It means that it is an internal and abstract representation that is not supposed to be observed by humans.

Definition of Latent Space by Panagiotis Antoniadis in this article:

Formally, a latent space is defined as an abstract multi-dimensional space that encodes a meaningful internal representation of externally observed events.

CLIP was trained to map texts and images to a meaningful shared latent representation such that similar contents (eg related image/caption pairs) have a high cosine similarity in the latent space.

A potential cause for the hidden vocabulary of models based on CLIP, is the almost random mapping of (arguably) never-seen words such as Apoploe vesrreaitais.

Latent representations of unseen data following the same distribution as training data can be relevant and useful if the model has good generalization. But for unseen data that is purely random, such as the gibberish words in DALLE-2’s hidden vocabulary, there is to my knowledge no one-size-fits-all method to recognize or force a good latent representation.

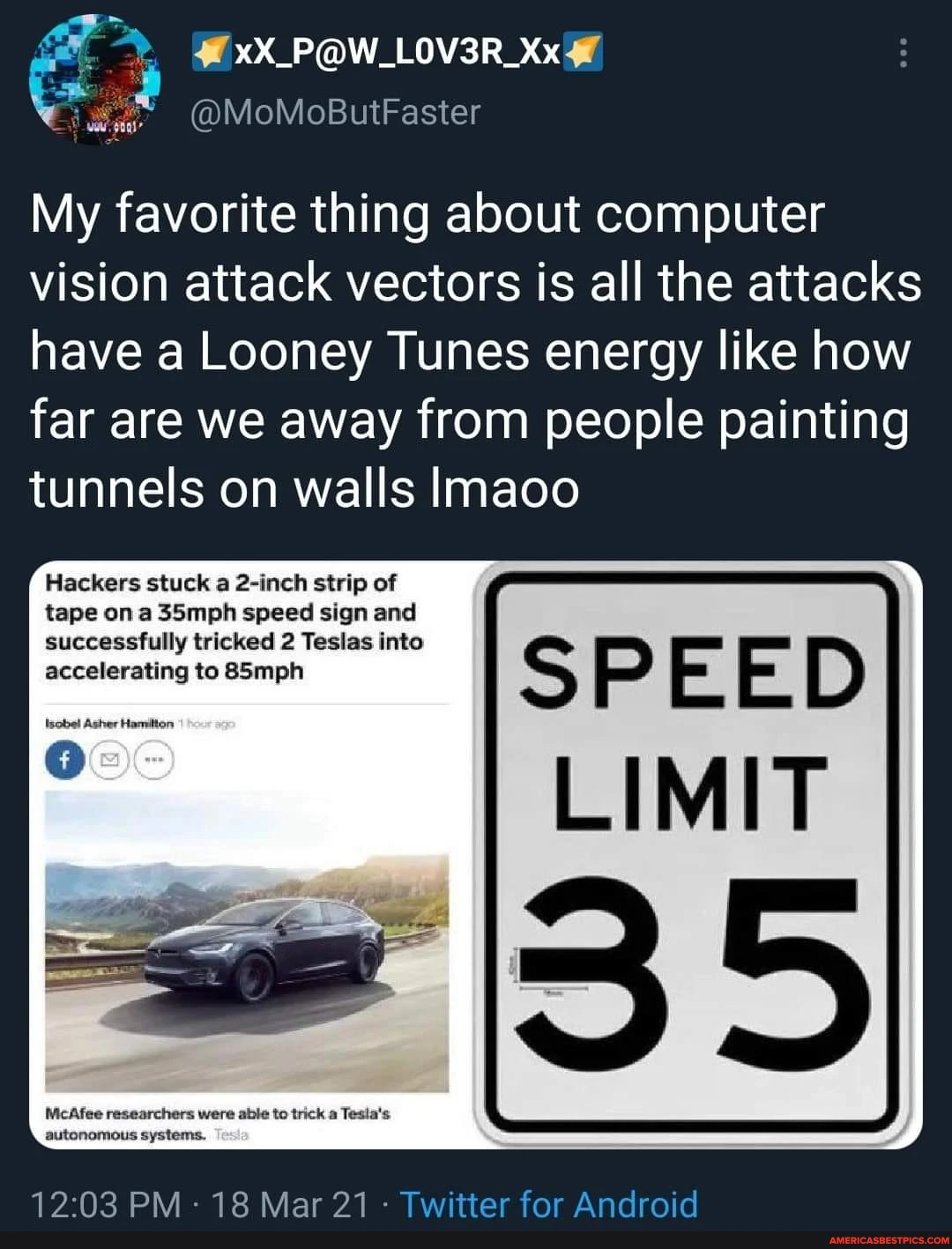

Potential misuse: Adversarial Machine Learning

A big threat in Deep Learning is the potential to use models’ limitations and biases to force false, or even hazardous, outputs.

The Wikipedia page for Adversarial Machine Learning reads:

To understand, note that most machine learning techniques are mostly designed to work on specific problem sets, under the assumption that the training and test data are generated from the same statistical distribution (IID). However, this assumption is often dangerously violated in practical high-stake applications, where users may purposely supply fabricated data that violates the statistical assumption.

Attacks in adversarial machine learning can be of different types:

- Black Box attacks: when you don’t have access to informations about the model, you just have access to the outputs for your inputs

- White Box attacks: you have access to the model parameters

A reason why a model such as DALLE-2 is hidden behind an API can be to block White Box attacks. Black Box attacks though are still possible, and the methodology behind the paper Discovering the Hidden Vocabulary of DALLE-2 can be considered as such.

By finding an attack vector (eg a piece of hidden vocabulary), it may become possible to generate explicit content with DALLE-2, even though the prompts are filtered, as stated in DALLE-2’s Risk and Limitations document.

Machine Learning Hygiene

A few decades ago, people working with computers were computer scientists, now most jobs need you to work with computers. Knowledge about computer science, programmation, and cybersecurity have become very valuable and common even for people that work jobs that aren’t strictly computer science-related.

One can argue that machine learning is on track to have the same future.

Nowadays those using machine learning in their job are mostly what we call machine learning engineers, but models tend to be used as ways to assists people in their jobs. You can find artists using models to generate ideas to work with, and journalists using models to generate extractive summaries.

Knowledge about machine learning such as latent spaces, hidden vocabularies and prompt engineering, might become valuable for a growing number of jobs and every-day uses.

Just like everyone using a computer should have a good cyber hygiene in order to prevent malicious events, everyone using a machine learning model should have a good machine learning hygiene. That could mean knowing about the limitations and biases of the models they use and the potential misuses.

In other words, learning the models’ language.